Question: With signs of accelerating effects from climate change, should $200-300 million of public money be invested in a new building to last less than a century on the Halifax waterfront?

When it comes to a new home for both the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (the so-called “Cultural Hub”), the provincial minister of Communities, Culture, and Heritage, Leo Glavine, says, “A waterfront location is still desirable.”

Glavine told the Halifax Examiner that while a couple of potential sites have been identified, no final decision will be made until “geo-technical work” is completed. That includes aerial surveys completed by the Halifax Regional Municipality last month. Elevation data will be used to “re-run” 3D models to determine the risk to waterfront structures from the one-two punch of global warming: rising sea level and storm surges.

“HRM does not yet have a formal plan for climate adaptation,” says Shannon Miedema, manager for energy and environment programs. “We’ve been screaming from the rooftops about climate change in my small office for a long time. At first, the big push was around cutting our GHG emissions. Now we need to prepare for consequences which to some extent are inevitable. Even if we stopped everything, we would still be seeing extreme weather. So we are about to develop an overarching climate strategy with targets to 2050 for cutting carbon and preparing for climate change.”

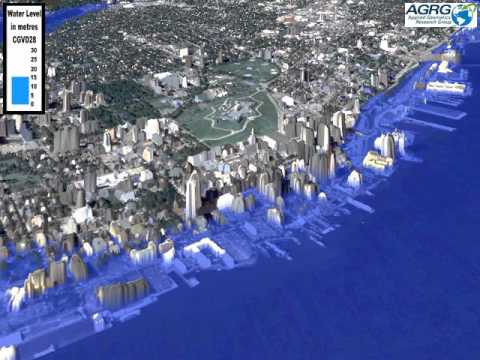

A motion to that effect is supposed to come before Council this Tuesday. If you have trouble visualizing what a rising sea level could do to waterfront properties in Halifax, watch this simulation on YouTube:

It shows how much flooding could take place from the Seaport Market to the Casino as water creeps (or surges) meter by meter. Under one scenario that assumes a 1.0-meter rise in sea level by 2100 (source: Geological Survey of Canada) combined with a 2.9-meter storm surge of Hurricane Juan magnitude, the video shows the ocean reaching to Lower and Upper Water Streets.

The modelling was done by Applied Geomatics of Middleton, NS. The same company has been hired to translate elevation data from laser or LIDAR scans into models that will then create flood maps and “land use vulnerability assessments.” At a shared cost of $2.8 million between Ottawa and HRM, Miedema says the new information should be available next fall to anyone who owns a coastal property.

“We are very interested in what the municipality’s new mapping is going to come back with,” says Peter Bigelow, head of planning for Develop Nova Scotia (formerly the Waterfront Development Corporation), which owns and leases land on behalf of the Province. “There is probably going to be a new number or standard for planning purposes.”

For example, the city currently requires only residential buildings along the Harbour — such as King’s Wharf on the Dartmouth side or Bishop’s Landing in Halifax — to build 3.8 meters higher than an imaginary line known as CGVD (Canadian Geodetic Vertical Datum 28), sometimes called the “vertical setback.” That height above highwater is supposed to protect buildings from flooding until 2100 — unless of course, global warming happens and seal level rise faster than predicted, and storms become frequent and more extreme.

But here’s the rub: government and commercial buildings have no such restrictions.

“We could raise the number (the 3.8-meter vertical setback) or we could make the number apply to more things, such as new commercial or government buildings,” says Miedema. “The regional plan can be reviewed at any time to make the change.”

According to both Miedema and Peter Bigelow of Develop NS, the $200 million Queen’s Marque development rising on the waterfront near the Maritime Museum exceeds the 3.8-meter-high water standard. Bigelow says the Armour Group also took care not to locate any critical infrastructure underground, but has encased 300 underground parking spaces in a “coffer” as part of storm-proofing measures to keep the building operating for the next 85 years.

Planners say global warming is causing all developers to rethink how they can make a business case for buildings likely to have a much shorter shelf life than the post offices and cathedrals of the past. Miedema notes that existing properties which have been flooded in the past (Salty’s and Murphy’s On The Waterfront, for example) may eventually become uninsurable, and force owners to raise or abandon them.

“Certainly, sea level rise needs to part of the conversation — and the costs associated with it,” says Bigelow. “But for someone to say, ‘let’s not put the Art Gallery on the waterfront because of sea level rise’… we’d better tell that to the owner of every property — including the Department of National Defence. Are we going to just abandon the waterfront, or find ways to protect it?”

Bigelow notes that during last summer’s public engagement process to envision a cultural hub on the waterfront, one of the consultants hired was talking to him from a city in the Netherlands. “It’s built eight meters below sea level,” muses Bigelow. “They’ve been dealing with this for centuries; it’s new here. What I think is the more relevant conversation is not what we are doing around individual properties, but what are the systems required to protect our shorelines and waterfronts that include our heritage and industry?”

Tom Smart has some practical experience in this area. He’s director of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, whose riverside location on the St. John River makes it vulnerable to spring flooding nearly every year. Although thousands of homes and businesses were damaged by water when the river burst its banks last spring, the Beaverbrook stayed dry. Smart, who had just arrived in Fredericton from Winnipeg (whose Gallery withstood massive flooding in 1997) says he has the utmost respect for nature.

“It’s by good management and not by good luck that we were able to keep the building and its contents safe during the flood,” says Smart. The riverbank had been shored up to divert water, and the Gallery’s foundation is protected by an underground casing. “A high-volume pump installed between the walls of the casing and the foundation worked perfectly to reduce hydrostatic pressure underground,” says Smart, who held “flood drills” before the event itself. He also credits a diking system made by a Dutch company with preventing water that rose 12-18 inches from breaching the walls of the gallery’s new wing.

Smart — who happened to be in Halifax the night Hurricane Juan blew through — saw that storm’s devastation. He also appreciates that the waterfront might be a tempting location to showcase a new Art Gallery. He suggests consulting the professionals, including Emergency Management officials, before selecting the site. “I’m a real proponent of (a) having a good plan and (b) taking the advice of the people whose profession it is to model these potential catastrophes and to really listen to them carefully,” Smart says, “because they have sophisticated systems that can really measure risk in an accurate way.”

“The world lives by the water,” reflects HRM’s Shannon Miedema. “Everyone wants to be there — tourists, businesses, residents. We don’t want to retreat when there are no issues with being there today. The challenge is trying to find the balance for the future.”

That balance needs to be struck soon. The estimated lifespan of new institutional buildings is diminishing, and oceanic threats to those built on coastal lands are increasing. Decisions about where — and how — to build public edifices like art galleries and art colleges costing hundreds of millions of dollars need to be made now by officials whose thinking is literally, in the words of the Tragically Hip song, “Ahead By A Century.”

The banks probably have stricter standards when deciding the terms of a loan.

Excellent point. If a bank wont finance it, then why on earth would taxpayers?

“But for someone to say, ‘let’s not put the Art Gallery on the waterfront because of sea level rise’… we’d better tell that to the owner of every property — including the Department of National Defence. Are we going to just abandon the waterfront, or find ways to protect it?”

This kind of abject denial and blatant hubris really does make me laugh. It is this kind of jackassery and sheer ignorance that has gotten us into this predicament in the first place. What a bad joke!

It would be interesting to see the same sea level rise/surge modelling applied to the Shannon Park district. Maybe Premier McNeil and his football pals have a plan for the proposed stadium to be convertible to a SeaWorld-type of aquarium. Oh, wait, all the popular aquarium species will be likely extinct by that time!

As planner for Waterfront Development, of course Mr. Bigelow is going to make such statements as he is quoted. He is completely off-base on both his points: It doesn’t make good fiscal sense in any measure to build public infrastructure in a high-risk area. The added capital cost to protect against sea level rise and dramatic storm surges would be better invested in the building’s cultural amenities such as better efficiency etc rather than a huge percentage of the project budget going into a sea wall. Also the comment he made about DND is extremely flippant for someone who is in a planning position. The DND infrastructure has been in place for years, long before the impacts of sea level rise were fully appreciated. They have the challenge of adapting their infrastructure to deal with rising sea levels because they have no choice. You can’t move a Navy inland.

As for Queen’s Marque, that is a private development and they are free to do whatever they think might (and I emphasize might) protect them from sea level rise.

Public infrastructure projects need to set an example for responsible investment of scarce resources, not throw a whole bunch of unnecessary money at building dykes, dams or whatever just to say they are on the waterfront.