This is the first article in a two-part series about ticks and tick-borne diseases in Nova Scotia — what we know about them and what we’re doing about them. Part 1 looks at some of the reasons for the tick population explosion and the increased incidence of Lyme disease, and what public health authorities are — or are not — doing about it.

Brenda Sterling-Goodwin has spent more than a decade trying — mostly in vain — to get the medical community to recognize the gravity and complexity of Lyme disease, the debilitating tick-borne illness caused by species of Borrelia bacteria.

Sterling-Goodwin also spends an enormous amount of time communicating with tick researchers and studying about Lyme disease — the black-legged ticks (also called deer ticks) that transmit it, the hosts on which ticks feed at each stage of their complex life cycle, the bacteria that cause it, the less-than-effective tests that are supposed to detect it, how it can be prevented in people and their pets, what they should do when bitten by a tick — and then sharing her knowledge with the public.

She promotes tick awareness groups in Canada, and tells the Halifax Examiner she has written 50 articles on the subject, many published in the Pictou Advocate. Her mantra is “Education is Key!”

Sterling-Goodwin, who grew up in on a dairy farm in southwestern Ontario, worked in vet clinics on weekends during her high school years, and she continued to do so during the summers when she was studying science at the University of Guelph. She recalls removing hundreds of ticks from cats at the clinics where she worked over the years, often without gloves, and with cuts and scratches on her hands.

At some point in the late 1990s, she had the misfortune to come in contact with Borrelia bacteria from an infected tick. In 1997 she began to notice the early symptoms of Lyme disease, among them fatigue, headaches, vision problems, and shifting discomfort in her legs.

“I was a farm girl, so I had a high pain threshold,” Sterling-Goodwin says.

But the symptoms just wouldn’t go away.

At first, she says, she was told she had “presumptive” multiple sclerosis. It wasn’t until 2006, two years after she had to stop working because of the symptoms, that she was finally diagnosed with Lyme disease. The same year, she began to use a wheelchair.

“I knew what I had before that,” she tells the Examiner. “But no one would listen. My GP dismissed me. People have to fight for testing and Canadian testing is wrong about 38% to 68% of the time because they test for only one strain of Borrelia.”

In a recent opinion piece, “Time to take Lyme disease seriously,” Sterling-Goodwin notes that it is not a new disease, and laments the fact that the medical community has failed to do what is needed to understand and deal with it.

Writes Sterling-Goodwin:

The bacteria Borrelia that causes Lyme can be vector borne and has been around for a long time, it was found in the remains of Ötzi the Iceman from the Bronze Age 5,300 years ago. It was in the late 1970s that Lyme became more prevalent and on the radar of some doctors. The group of bacteria of growing concern is Borrelia, which is a spirochete which has become epidemic and is growing unchecked and being found worldwide.

Lyme disease, also referred to as “the great imitator,” is one of the most misunderstood and widely growing illnesses. Its symptoms resemble those of so many other diseases and because our conventional medical community continues to be misinformed, stricken patients fail to receive the Lyme disease treatment necessary to restore their health. Lyme disease is so generally misinterpreted, standard treatment can typically last only four to six weeks or less, with extensive treatment widely believed to be unwarranted.

Sterling-Goodwin also says, “Getting adequate treatment can be a challenge because of lack of knowledge and the limited IDSA [Infectious Disease Society of America] guidelines that are being followed by health care practitioners.”

If, after completing a prescribed treatment for Lyme you still have symptoms, she says, “you are often told ‘you are cured and must have something else wrong.’”

That, she believes, is the wrong answer.

“The problem is growing and no one is listening,” says Sterling-Goodwin.

Number of Lyme disease cases “exploding” in NS

The problem certainly is growing.

According to Jason Stull, infectious disease specialist and assistant professor at the Atlantic Veterinary College at the University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown, the number of human Lyme cases in Nova Scotia is “exploding.” There is a similar increase in dogs, but Stull notes there are vaccines and preventative treatments for pets.

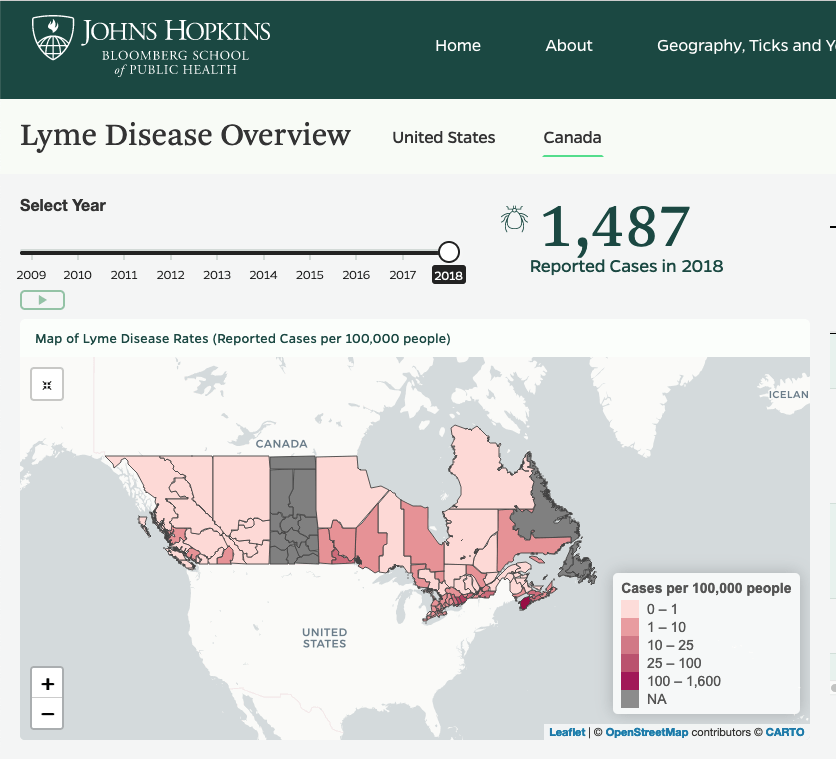

By 2018, Nova Scotia had 34.4 cases of Lyme disease per 100,000 people, nearly 10 times the incidence in Ontario, the province with the second highest incidence in Canada. The incidence in southwest Nova Scotia was even higher than the provincial average.

Statistics provided by the Companion Animal Parasites Council show that the incidence of Lyme in dogs has also been rising rapidly in Nova Scotia, and the province has the highest rate of canine Lyme disease in Canada.

More ticks, more risks

In the winter of 2003, the Nova Scotia government published a document called “Preparing for tick season,” which looked at ticks and Lyme disease, noting that the very first human case of the disease had been recorded and that a Lyme-positive deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) had been found in Antigonish County the previous summer.

It noted that the disease had first been detected in Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975, and had since then been detected in most of North America, Asia, and Europe.

The document made it sound all very simple and straightforward, stating that, “In Nova Scotia, the deer tick is the primary carrier of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent that causes Lyme Disease.” It offered this primer on the life cycle of deer or black-legged ticks:

The deer tick is a three-host tick and takes two years to complete its life cycle. Eggs are laid in early spring amongst vegetation on the forest floor. Tiny, six-legged larvae emerge in early summer with larval activity at its highest in August. The larvae feed on a variety of hosts, including birds and small mammals. In the fall the engorged larvae drop off their hosts. The following spring the larvae molt into the larger nymph stage. Throughout the summer the nymphs feed on birds and larger mammals such as deer, dogs, and people. This is the stage at which they are most likely to be transported to new regions via migrating birds and animals. In the fall, the engorged nymph drops off its host to the forest floor and transforms into the adult stage. Adults remain active into the mild days of winter, feeding primarily on deer and larger mammals.

In 2012, the Nova Scotia government published a report on Lyme disease epidemiology and surveillance in the province, which stated that, “since the first cases were reported in 2002, the annual number of reported cases of Lyme disease in Nova Scotia has been increasing.”

The report acknowledged the growing incidence and awareness of ticks and Lyme:

The increase in cases is likely due to a number of factors including an increase in the number of tick populations established in Nova Scotia, increases in the sizes of established tick populations, and an increase in awareness among individuals and physicians leading to increased diagnosis and reporting of Lyme disease.

…

Climate change models predict that Nova Scotia is very close to having a suitable climate for tick establishment across the entire province. Local ecology, including suitable habitat, host availability and other factors, will determine the extent to which tick populations will expand and where new populations will establish.

The report said that the province had “implemented integrated human and tick surveillance” for new endemic areas. But that was back in 2012.

In 2019, the provincial Department of Health and Wellness produced a map showing the estimated risk areas for Lyme disease in Nova Scotia, which has the dubious distinction of being the only province in the country where the risk is province-wide.

Ticking off Lyme experts

The Halifax Examiner contacted the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness and requested an interview to get updated information on tick populations in the province, the health risks they pose, and any research ongoing to minimize those risks, or new testing and treatment regimes. Even after a reminder email, that request has not yet been granted. Nor has there been any response to a third email with a list of questions.[1]

In January 2019, Nova Scotia’s Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. Robert Strang earned the wrath of some tick and Lyme experts when he retweeted a tweet from an anonymous, conspiracy-theory-spreading account inappropriately called @LymeScience. The tweet dismissed chronic Lyme disease as pseudoscience and supported by a chronic Lyme cult.

Saltwire journalist Andrew Rankin contacted Strang about the retweet, but he declined comment. Wrote Rankin:

Strang told the Herald last September that the standard short-term antibiotic treatment for Lyme in the province is effective. He declined to say chronic Lyme exists and that bacteria could persist after a short course of antibiotics. But he said in some cases people have residual symptoms after being treated.

Nova Scotia Health’s website provides patient information on Lyme disease, which also appears to downplay the likelihood of long-term or chronic Lyme, saying that symptoms only continue “occasionally” if it is not treated early:

Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics. Early treatment almost always results in a full recovery. Lyme disease is rarely life threatening, but if it is not treated, serious symptoms or illnesses may develop. These are not common, but can include facial palsy, heart problems, or chronic joint problems such as arthritis. Lyme disease symptoms can also be treated by antibiotics. Occasionally, the symptoms may continue if treatment has been delayed for too long.

“Chronic Lyme is a real thing”

Vett Lloyd is professor of biology at Mount Allison University and principal researcher at the Lloyd Tick Lab that she founded at the university. For her, there is no question about the existence of chronic Lyme disease.

“Chronic Lyme disease is a real thing,” Lloyd tells the Examiner in an interview.

It’s also a complex thing. Lloyd explains:

There is dispute about what it “should” be called, but not that people are ill and suffering. Chronic Lyme is a patient-generated term. It encompasses three major biological situations, undiagnosed and untreated Lyme disease, ongoing damage, immune dysregulation or other medical problems after treatment, and under-treated Lyme disease that does not eliminate infection.

Lloyd points out in a follow-up email that sometimes the medical community can and should learn from patients, as they are doing with the COVID-19 pandemic:

There may be pushback against having patients define the term rather than the medical community, but that being both acceptable and desirable is part of the societal shift towards social justice. For context, the term “long COVID” and the term “COVID long haulers” was generated by the patient community … Aside from the relative brevity and clarity of the patient-generated term, it is increasingly recognized that … it is appropriate for patients to name diseases.

This isn’t actually new, syndromes traditionally named after the physician who first described them – i.e. Downs syndrome — are now being renamed more scientifically or by patient groups (in this case, scientifically — trisomy 21). [2]

From Lyme survivor to Lyme researcher

Lloyd is herself a treated Lyme disease survivor.

She contracted the disease from a tick nine years ago when she was gardening in New Brunswick, in a time and place where there was very little awareness of ticks or Lyme disease.

“It was horrible, frightening, certainly the worst disease I’ve had,” she tells the Examiner. “It took me a long time — five and a half years — to recover my health, and a lot of that was me getting partial treatment and looking for more treatment. I could only do that because I have two areas of privilege”:

One is that a lot of wildlife biologists I worked with were more alert than I was and gave me correct information. So, I pursued that diagnosis and was able to travel to get treatment.

But for the most part, my health has fully recovered. But I’m one of the lucky ones because I had friends who pushed me in the right direction and I had the money to get the right treatment.

Once she recovered her health, Lloyd decided to turn her scientific expertise to the study of ticks, as there are very few labs specialized in Lyme disease. Initially, she says, she thought she would just spend a summer on the work to show there were ticks and health risks in the area, and that she would let public health know and they would be “really grateful and everything would be fixed.”

“It didn’t work out quite like that,” says Lloyd, who has been studying ticks ever since.

Throughout that time, tick populations and the incidence of Lyme disease have been growing, nowhere more so in Canada than in Nova Scotia.

A competition Nova Scotia doesn’t want to win

Lloyd points out that in absolute numbers there are probably more ticks and people getting ill in southern Ontario, but there are also more people in Ontario.

“So on a per capita basis, Nova Scotia does win for cases of Lyme disease,” Lloyd says. “It’s not a contest Nova Scotia really wants to win.”

Lloyd says those numbers do not tell the whole story; far from it:

You also have to remember that not every case is going to be diagnosed. So, the people who get diagnosed, actually those are the lucky ones because hopefully that leads to the treatment, which leads to the disease being arrested or eliminated.

She says that until 2009 when the disease became “reportable,” family doctors may or may not have recognized Lyme disease, but they would have had no one to tell, or any way to log it. Even if they treated patients with antibiotics, it would not have been recorded.

And there are still huge problems with how the disease is diagnosed and reported.

Actual numbers could be much, much higher

In 2018, Lloyd co-authored a paper with University of Calgary clinical associate professor of medicine, Ralph Hawkins, revealing that “public health information is significantly under-detecting and under-reporting human Lyme cases across Canada,” and that actual numbers could be 10.2 to 28 times higher than actually reported.

Lloyd and Hawkins calculated that, “only approximately 1 of every 6 infected patients for whom laboratory testing is ordered receives a formal diagnoses of Lyme disease.”

The authors attributed this to a range of factors — and failures — in the way Lyme disease is handled:

Causes of the discrepancies between reported cases and predicted actual cases may include undetected genetic diversity of Borrelia in Canada leading to failed serological detection of infection, failure to consider and initiate serological testing of patients, and failure to report clinically diagnosed acute cases. As these surveillance criteria are used to inform clinical and public health decisions, this under-detection will impact diagnosis and treatment of Canadian Lyme disease patients.

Lloyd and Hawkins concluded:

Under-estimation of the problem likely results in inadequate allocation of health care and research resources but most importantly, significant health, social and economic costs from impaired health, quality of life, ability to function and to contribute to society, and the attendant personal suffering for those who truly have Lyme disease.

A 2019 paper by Public Health Agency of Canada senior research scientist Nicholas H. Ogden and 12 co-authors appears to contradict the findings that fewer than 10% of Lyme cases are actually reported, arguing that, “a high degree of under-reporting in Canada is unlikely.”

However, in the very next sentence, Ogden et al. admit that under-reporting may still mean that two-thirds of actual cases are missed:

We speculate that approximately one third of cases are reported in regions of emergence of Lyme disease, although prospective studies are needed to fully quantify under-reporting. In the meantime, surveillance continues to identify and track the ongoing emergence of Lyme disease, and the risk to the public, in Canada.

Ogden and his co-authors note that, “Lyme disease is emerging in Canada due to expansion of the range of the tick vector Ixodes scapularis [black-legged or deer tick] from the United States,” and that Lyme incidence had “increased from 144 cases in 2009 to 2025 in 2017.”

They call the risk of Lyme disease an “emerging” one.

Others argue that it has already emerged, and is only set to get worse, as the populations of ticks that spread disease continue to expand.

Ticks and climate change

Lloyd says that climate change is a big part of the increase in the tick population in Nova Scotia, and the related increase in the incidence of Lyme disease.

The tick expansion we have already seen has occurred with a rise in the global average temperature of just over 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and the rate of warming is accelerating. The global average temperate is predicted to continue to rise 2.7 to 3.1 degrees above pre-industrial levels this century.

The Lyme problem is not related to the 20 or so tick species that are native to Nova Scotia, she says, species that have specific hosts, living “on one type of wild animal and rarely bother humans.” The rabbit tick is an example of that.

“The real problems for people are the deer tick or the black legged tick, both are the same beast,” says Lloyd. “That’s the one that carries Lyme disease.”

She continues:

The other ticks that we’ll often find on people is the American Dog Tick, which is also called the wood tick. That is very abundant in Nova Scotia and invading New Brunswick. But mostly that’s an issue in Nova Scotia. So there’s a lot of that tick around. It doesn’t transmit Lyme disease particularly well. That may be the odd case here or there, but it’s not considered a vector. It does carry other diseases.

It’s unclear when these two species — dog and deer ticks — got established in Nova Scotia, according to Lloyd. The dog tick was probably introduced 100 years ago. But the deer tick came more recently. It was first documented in Long Point, Ontario, says Lloyd, and was certainly established there in the 1980s. However, she says that some people in the Nova Scotia report being bitten by ticks and getting Lyme disease as far back as the 1970s, possibly from sporadic ticks that dropped off birds.

Lloyd says that while moose and rodents do spread ticks when they move, the main way ticks are introduced in the Maritimes is on migratory animals, which move much faster. She offers this lyrical explanation of tick lives and “tick love:”

In spring, birds migrate north and they tend to go up coasts, travelling up the American seaboard. They’re going to be picking up the baby ticks, the nymphs that come here. The [nymph] ticks have enjoyed not only the ride, but a blood meal, sort of first class service. Then once they’re full, they drop off. And once they drop off they moult and become adults, and if you get a male and a female near each other and there’s food around, a little tick love ensues and you get more ticks. I’d like to say that I really don’t know about the emotional state of ticks. However, certainly there are babies.

There has always been a steady supply of ticks coming up in the spring from warmer climates, Lloyd says, but long winters prevented them from multiplying:

With the more conventional Maritime winter, the winters that older people will recall, there was snow up to here and there was snow from November through to May. If the ticks were buried under snow, some of them died. But it actually has to be really cold to kill a tick. Mostly if they’re buried [under the snow longer into the spring], they don’t have enough time during the summer to go through enough of a life cycle. So eventually they die out.

With climate change, our winters are shorter and they’re also warmer. So the ticks can get out and start looking for meals as soon as it’s four degrees [Celsius]; they really like 10 to 18 degrees. So with our spring coming earlier and our fall lasting later, they start earlier getting a blood meal. They end earlier, so they can get through more of their life cycle, get more food, make more babies. And bear in mind that a well-fed female can make about 3,000 babies.

Lloyd says a warmer climate means:

The rodent population has also increased, so there’s more food for ticks. The deer tick is — not that surprisingly — partial to deer, and there’s a lot of blood in deer. The same is true of coyotes and foxes and moose, and pretty much all the big mammals. There’s a lot of lot of food there. It’s also a great place for one tick to meet another tick. It’s kind of your singles’ bar for ticks.

Ticks turn to human hosts, says Lloyd, “when they kind of run out of the their natural food and they grab a pet or they start feeding from the person. And when the population gets really high, that’s going to happen more often.”

Lloyd says there is always a “certain amount of exponential population growth whenever a new species gets established because the local ecology hasn’t adapted to them.” She says it is unlikely that the population of deer ticks is going to drop again any time soon, as there just aren’t any real predators, with the exception of chickens and guinea fowl, and some ground-feeding birds.

Nova Scotia’s tick problem is already evident, and now it is spreading into New Brunswick, she adds.

Lots of Lyme but no tick testing in NS

Lloyd says the focus of the Public Health Agency of Canada and its provincial partners has been the surveillance of tick populations, with tick testing done by the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg. But now that they’ve found the problem, the question is to find funding and ways to deal with it.

“That ticks are here is actually only the start, not the end,” she says. “The funding was set up for surveillance.”

The Lloyd Tick Lab at Mount Allison University formerly offered free testing for Lyme and other pathogens in ticks submitted by the public. They were able to do so thanks to “research grants and the generosity of private donors,” who chose to remain anonymous, Lloyd says. That funding is exhausted, so the lab now works with a private company to do the testing and charges a fee (starting at $50) to cover the costs of the re-agents required for the testing, although Lloyd and the students volunteer their time.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has a webpage devoted to “removing and submitting ticks for testing.” It includes information on how to save the ticks and where people across the country can send them for testing. Most provinces have public health laboratories that accept submissions from the public and provide tick testing.

Surprisingly, Nova Scotia, with the highest incidence of Lyme disease in the country, is not one of those.

Nova Scotians can either send ticks to the Public Healthy Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory, or they can pay for testing at the Lloyd Tick Lab in New Brunswick.

Lloyd says that 15% to 20% of the ticks sent to the Lloyd Tick Lab come from Nova Scotia.

She believes there is a need not just for more public funding, but also more public awareness of Lyme:

Before COVID, there was a comparison made in the [United] States saying that there were roughly six Lyme disease infections for every HIV infection. But if you look at the amount of public awareness about sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV … and Lyme disease, that’s discordant. The funding for research into, say, a vaccine or treatment modalities [for Lyme] hugely lags behind … A lot of it is based on the States’ bad history of minimizing the disease, the massive argument about the appropriate treatment regime, which really boils down to “how long do you take antibiotics?” And honestly, I don’t think patients really care. They just want to get better. People in the community just want to not get it or at least want to be treated. And if something goes wrong, they want to be diagnosed and treated early and effectively. So we need much more research into the treatment part of the puzzle. And I do think that’s going to be coming from the States. They’ve been dealing with Lyme disease, for better or for worse, longer than Canada has.

Lunenburg on the Lyme frontline

Lloyd says that no one knows what percentage of Lyme cases lead to death, but she says that without the right treatment, the prognosis can be bad:

The bacteria spread through the body and they multiply, and they can invade organs. Some organs can tolerate them. So if they end up in your joints, that’s going to cause inflammation. Pain makes your life miserable but it probably won’t kill you. If they end up in your heart and you get inflammation there, that’s a much worse outcome. That leads to something called Lyme carditis, which is basically inflammation of the heart due to Lyme disease. That’s fatal.

The bacteria can also impact the liver, she says, which “is called a vital organ for a reason.” And, she adds:

Very well studied in Europe and much less so here is neuroborreliosis. This cheerful medical term basically means the Lyme disease bacteria get into the brain and that’s going to cause inflammation and all kinds of bad things. You don’t actually want bacteria in your brain. That can lead to slower forms of neuro-degeneration, which contributes to death.

In the Lyme “hot spots” like Lunenburg, Lloyd says that the medical profession is getting used to seeing Lyme and dealing with it quickly and effectively. [3]

This is thanks, in large part, to the people in the community who are taking the lead in Lyme awareness and prevention.

[1] On June 18, the Examiner contacted the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness to request an interview with someone from the Department or researchers perhaps doing research in collaboration with the department, on current tick population and distribution statistics and changes, the various health risks they pose to humans and animals (particularly dogs and cats), and the province’s ongoing research on these issues and efforts to minimize these health risks. One June 21, a reminder email was sent, and the department spokesperson replied, “I’ll be in touch.” That didn’t happen, however, so on June 27, the Examiner sent the following questions. Again, there was no reply.

- Does Nova Scotia offer testing of ticks for pathogens (including Lyme disease) that are submitted by the public? Is it free? If not, how much does it cost?

- If not, did the province previously offer this service, and when / why was it stopped ?

- If not, why is there no such service?

- Given the prevalence of ticks and Lyme disease in Nova Scotia, is there a plan to start offering tick testing? And if so, would it be free or would those submitting ticks be charged?

- Nova Scotia has the highest incidence per capita of Lyme disease in Canada but I have not seen any notices in public parks or areas, or in the media, informing Nova Scotians or visitors of the risks these pose. Has the province put up notices anywhere in public places? If so, where? If not, why not? Are there plans to do so?

- Is the province considering any public awareness initiative of the risks of tick-borne diseases, and how to prevent them? If so, for when and what would this entail?

[2] Yvette d’Entremont wrote an in-depth article on long-haul COVID-19 for the Halifax Examiner, and interviewed Vett Lloyd for that article.

[3] In 2019, Lunenburg Doc Fest’s Seniors Documentary Workshop resulted in the creation of an important and enlightening film, “Faces of Lyme,” which profiles several Nova Scotians’ personal experiences with Lyme, including that of Rob Murray, who is featured in Part 2 of this series. The film also offers a great deal of important information about protection from ticks, and practical measures people in Nova Scotia, and the authorities, can take. It also offers some light relief from a difficult subject: viewers learn that ticks checks are also known as “Lunenburg foreplay.”

The story made me itch all over. I first heard of deer ticks and Lyme disease while working in the Annapolis Valley in the early 70s – it was a new thing. Ticks were rampant here in northern NS this spring and early summer, so that getting five or six on me per week was normal. They were brown dog ticks, as near as I could tell under a magnifying glass – a few crawling on me and two embedded. Haven’t seen any in a couple of weeks. I guess it would be foolish to hope they just stay away.

Forest fragmentation/clearcutting are likely factors contributing to the rapid increase in black-legged ticks in NS. View http://nsforestnotes.ca/2018/06/16/could-forest-fragmentation-be-a-factor-in-the-high-incidence-of-blacklegged-ticklyme-in-nova-scotia/

For those of you that couldn’t make the Bridgewater Lyme Conference in November of 2018, the majority of the presentations are on-line on You-Tube at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCO3Bd0xDKwUcoBMGyqoDsUg or on the “Lunenburg Lyme Association” Facebook page.

There were also Lyme Information Sessions in Halifax in 2017 and 2018. Unfortunately, the 2017 taping was done incorrectly and could not be shared, but the 2018 presentations can be found here – https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCe2yM3BPfLmlUMCM493GC1w. This is my YouTube channel – “Nova Scotia Lyme Awareness”. You can find many more videos, including the Bridgewater Lyme Conference ones, under the Playlist “All About Ticks, and What They Carry, in Nova Scotia”.

Great article, I look forward to the next part!