Nova Scotia has long been a popular place not just for settlers, but in the last century it also became a popular place for non-residents — including many well-heeled Americans and Europeans — to purchase properties.[1]

For decades, scholars and successive governments have debated the issue of non-resident land ownership in a province with relatively little Crown land, with waterfronts being carved up into private properties that reduce public access to Nova Scotia shorelines.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a real estate boom in Nova Scotia, including most rural counties, as people from urban centres, elsewhere in Canada and abroad, looked for ways to escape crowded urban areas.

A few months into the pandemic, the German magazine, Der Spiegel, broke the story that some right-wing conspiracy theorists were marketing Cape Breton to like-minded German-speaking Europeans, which added yet another dimension to long-standing questions about non-resident land ownership in Nova Scotia.

In this three-part series, the Halifax Examiner follows up on its 2020 coverage and looks into some of these questions it raises, even as the province prepares to change the property tax rate for non-resident owners.

This, the final of three articles, looks at previous efforts to come to grips with the question of land ownership regulation in Nova Scotia, what it means for affordability of properties, and why it’s all been so contentious for so long.

Read Part 1 here.

Read Part 2 here.

It was a spring day, and as they’d been doing for some weeks, Jan and Paul (not their real names) were driving around looking for land on the South Shore of Nova Scotia, where Jan had spent a good part of her childhood.

Both were living and working in Halifax, and wanted a property they could call their own, where they would settle down and eventually retire. They had been scouting out properties for weeks, and had yet to find a place they could afford. For many years, the South Shore had been popular with American and European buyers who had no problem paying hefty prices for oceanfront properties.

“One day we were driving out near Terence Bay,” Jan recalled for the Halifax Examiner. “And we saw this sign that said ‘lots for sale’ on a dirt road that seemed to lead to the waterfront. So we just started driving. The gate was open.”

Suddenly another vehicle came out of nowhere and cut them off. The woman driver stopped her car, slammed the door, and approached their open window, angrily informing them they were on private property.

“We said we were sorry but that we had seen a sign that there were lots for sale, and we told her we were potential buyers,” Jan said.

The woman, who had a strong German accent, was still angry, and proclaimed loudly, “We don’t sell to Canadians.”

She said the lots were only for Europeans.

Jan and Paul turned around and headed back to the main road.

Jan, a fifth generation Nova Scotian, was in tears.

This happened back in the mid-1990s, but Jan remembers it as if it were yesterday, especially her visceral reaction to being told that Canadians were not welcome to buy land in … Nova Scotia.

A new tax levy for non-residents?

Non-resident land ownership in Nova Scotia has been a contentious issue for decades.

The question of whether those who own land, reside and pay taxes in Nova Scotia should pay lower property taxes than those who do not has been debated, discussed, and disagreed on since the 1960s.

In 2000, the province proposed legislation that would have enabled municipalities to levy additional taxes on non-resident property owners, but the government didn’t proclaim that part of the Municipal Government Act, “pending further discussions with the public.”

The following year the province set up a “voluntary planning board on non-resident land ownership” to carry out those consultations, because, as the press release at the time stated:

Nova Scotians have voiced real concerns about rising property tax bills, higher land prices and reduced access to ocean and inland waters,” said Mr. [Jim] Moir [chair of the Voluntary Planning Task Force on Non-Resident Land Ownership], of Mill Village, Queens Co. “Yet we’re also aware of the positive effect of the investment dollars flowing into our province from non-residents who are building homes and providing employment for many of our fellow citizens. These are some of the issues we need to look at.”

The task force came, listened, reported, and went, and little changed, something we’ll come back to.

The legislation that would have allowed municipalities to hike taxes for non-resident landowners was never proclaimed.

Now, 20 years later, it looks as if the government of Tim Houston has decided, just like that, to impose a levy on property taxes for non-residents who own property in Nova Scotia.

In his September 14, 2021 mandate letter to Nova Scotia’s new Minister of Finance and Treasury Board, Premier Tim Houston listed eight tasks that he expects Allan MacMaster to accomplish over the next four years.

One of those is to “impose a levy on every non-Nova Scotian taxpayer held property in Nova Scotia of an additional $2 per $100 of assessed property value.”

But what exactly does that awkwardly-worded task in the mandate letter actually mean? Who are these “non-Nova Scotian” taxpayers who own property, how many of them are there, is the province able to keep track of them, and how much extra revenue will this generate for the province?

Province mum on what it all means

At this point, the province isn’t saying.

In response to a series of questions about the mechanisms that might be used to identify non-Nova Scotia taxpayers and how many such landowners there might be in the province, spokesperson for the Department of Finance, Gary Andrea replied:

… the department is working on developing policy around the property related tax measures for non-residents that are included in the Minister of Finance and Treasury Board’s Mandate Letter. Once that policy is ready to announce we will provide details on how this program will be delivered.

Andrea did not respond to a request for an interview with someone in the department who could explain — even just as background and not for attribution — some of the ins and outs of any policy that might affect non-resident landowners.

Andrea also declined to clarify whether “non-Nova Scotia taxpayer held property” meant people who are not paying income taxes in the province, saying only, “That is part of the process that is now underway.”[2]

The Halifax Examiner also approached the Department of Municipal Affairs and Housing, as property taxes are paid to municipal governments.

Asked how the decision was made to impose a levy, what calculations went into deciding on the amount, and what the estimated increased in property taxes will be, however, Krista Higdon, spokesperson for the Department of Municipal Affairs and Housing, replied, “These are platform commitments from the government and will be announced when the policies are in place.”

Higdon said only that there are no references to non-resident landowners in the Municipal Government Act.

However, Higdon said, “The Assessment Act (section 45A) does reference that the Capped Assessment Program does not apply to non-residents.”

Data on non-residents incomplete

While “non-resident” can have different meanings, the relevant definition here seems to be the one in the Land Registration Administration Regulations: “an individual who resides outside the Province for 183 days or more in a calendar year,” or someone who intends to do so.

According to Blaise Theriault, spokesperson for the Department of Service Nova Scotia and Internal Affairs, information about who is and who is not a resident of the province is self-reported by the purchaser when they buy property, and is only collected for parcels of land that have been added to the titles system.

“The process of migrating a land title into the system is triggered by several factors, with the most common being the sale of land,” said Theriault. “Currently about 63% of parcels in Nova Scotia are in the system.” Theriault explained:

The Province has collected information on the residency status of land owners whose land has been migrated into the land titles system since 2005. The system is built to show a moment in time and does not show trends of non-residents over time.

As for which counties had the highest percentage of non-resident landownership, based on the incomplete data in the system, Theriault said:

Halifax County (0.64% of the Province’s total migrated parcels); Lunenburg County (0.63% of the Province’s total migrated parcels); and Inverness County (0.55% of the Province’s total migrated parcels).

Theriault said that of parcels in the land titles system, “approximately 5% of the registered land mass of Nova Scotia is owned by non-residents or a mix of residents and non-residents.”

Asked how the government would be able to implement a levy on non-Nova Scotian taxpayer-held property, given that nearly 40% of land titles have yet to be migrated into the system where residency status would be recorded, Theriault replied that those questions would have to be asked of the Department of Finance.

But, as noted earlier, the Department of Finance wasn’t prepared to answer questions about the new policy.

Nova Scotia Realtors also taken by surprise

The Halifax Examiner is not alone in its quest for more information about what the provincial government intends with its new levy.

It seems the Nova Scotia Association of Realtors (NSAR), which represents over 1,800 real estate brokers and salespeople across the province, is also unclear about it.

Speaking to the Examiner, NSAR president Donna Malone said of the proposed levy, “It seems like they’re going to penalize people who don’t pay tax in Nova Scotia.”

“I don’t know how easy it is to determine who those people are,” said Malone. “And there is already a deed transfer tax. So I presume they’re proposing a levy of $2 per $100 [of assessment]. They must be planning to add that to the deed transfer tax that’s already in place.”

According to Access Nova Scotia:

Property taxes differ from the Deed Transfer Tax and are determined by the municipality based on the assessed value of a property. The Property Valuation Services Corporation (PVSC) determines your property’s market value and your municipality uses that assessed value to calculate your property tax bill.

Malone pointed out that the deed transfer tax is a municipal tax that differs from one municipality to another. “They set their own rate on that,” she explained. “In some municipalities it’s 1%, 1.25%, 1.5%.” Malone said the deed transfer tax is paid on the purchase of the property, but she doesn’t know where the proposed levy will be charged.

“Anybody purchasing a property is paying that anyway. So are they saying now they will add $2 per $100 of assessed value to that? Or are they talking about bringing some type of tax that’s like an annual tax, or something?

Malone said that in early October, NSAR reached out to the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Housing, and Premier Tim Houston, asking for a meeting to “discuss the impact that government policies would have on the real estate market and housing.”

“We are the voice of the real estate industry in Nova Scotia,” she said. “So we would like to have an opportunity to talk to the people who are making these decisions and to kind of get an understanding of where they want to go and how they think they’re going to get there.” Malone said that she would like government to reach out to experts “in the industries that they’re tinkering with before making final decisions.”

Malone said that NSAR believes “everybody has the right to a safe, affordable home.” She doesn’t think there should be “additional financial burdens” on people who have homes in Nova Scotia, but who live somewhere else.

“If those owners are renting their properties out,” she said, “then any additional financial obligation that the government is going to put on those owners is going to be passed on to Nova Scotia residents who may be renting their property.”

Malone said that those who come for a few weeks or month of their year also contribute to the local economies of smaller communities.

“They help keep rural restaurants open and help support local business people,” said Malone. “They have their own health insurance and they buy gas, so there’s a financial benefit for these communities when people who don’t pay taxes here come and spend time here.”

Of course, as has been shown in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, not all those buying land in Nova Scotia are doing so with the intention of immigrating to or even vacationing in the province, and are purchasing land as an investment, or even a safe haven from their homelands in Europe, because of their own perceived fears of collapse or refugees of colour.

Asked about non-resident landowners who buy properties and just hold onto them, citing the examples of the sales of Cape Breton properties to European non-residents, Malone said that municipalities are governing bodies that could deal with these “sorts of things” on a “one-off basis where a municipality feels that something is a damage or detriment to their community.”

According to Malone:

There certainly is an impact to real estate when people of various financial means want to own the same property. I don’t think anybody could dispute that. But how much that affects whether or not somebody can find a home or have a home, I certainly don’t know. But I can tell you that in Nova Scotia, we still have properties for sale in all price ranges. So, yes, property prices have gone up. I would say yes, some of the increases have been caused by the various levels of financial means that people have. But I think a bigger part of what’s going on is supply. If there are enough homes for everybody who wants a home, then the competition for a home is low.

And does Malone think a differential property tax rate for residents and non-residents is a reasonable path for the province? Her reply:

I think the government should look at all options and look at the pros and the cons of each option. The current housing crisis is more about housing supply than it is about taxation or foreign owners or out-of-province owners, I think. So coming up with a good, solid plan for increasing housing supply, in the short term and the long term, I think is what the brain trust would be better served by, really focusing on that aspect.

Malone said the issue of non-resident land ownership is a complicated one. “If it were simple it would have been solved already,” she said.

“Please don’t sell Nova Scotia”

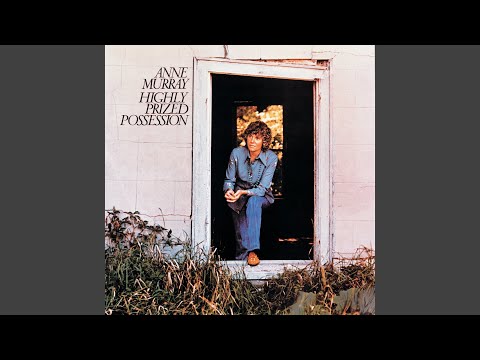

As mentioned earlier, the issue of non-resident land ownership in Nova Scotia is nothing new. Some of us (considerably) older people in the province may remember the song “Please Don’t Sell Nova Scotia,” written by Peter Pringle and released on an album in 1974 by Anne Murray, the title of which echoed a common concern even back then.

In 1998, a Dalhousie University student, Heather Breeze, wrote a Masters thesis entitled “Exploring the Implications of Non-Resident Land Ownership in Nova Scotia.” In it, she laid out the issues:

Concerns related to non-resident ownership fall under several different themes: the economy, natural resource management, society, and the environment. Countries all over the world and several provinces of Canada have legislation or regulations targeting non-resident owners …

Breeze looked at studies done in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s on non-resident landownership in Nova Scotia, including an earlier Masters thesis done in 1977 at Dalhousie University by the late Kell Antoft, who found that towards the end of the 1960s, “American buyers sharply increased the price of land in Nova Scotia.”

However, Breeze noted, despite the work of Antoft and the concerns raised by other writers before and since, Nova Scotia had “yet to develop a clear policy on non-resident land ownership,” nor did it “have any hard figures on the amount of land held by non-residents.”

And, she wrote, her own concerns about the issue came from travels in 1997, during which she met residents of coastal communities who talked to her “about people moving away and selling their homes to vacationers from out of town.” According to Breeze:

The residents were concerned about the impact of such land sales on the future of their communities. Their observations were reinforced by bilingual (English-German) real estate signs posted in Cape Breton, which represented overt marketing of the province to non-Nova Scotians.

Breeze undertook a special case study of Richmond County, looking specifically at some of the same issues detailed in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, including the carving up of the landscape into “subdivisions” — at that time by Rolf Bouman’s Canadian Pioneer Estates — that were being bought by seasonal residents from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

Breeze found that there was inadequate information on tax accounts, but using what was available, found that in the late 1990s non-residents accounted for about 17% of all the property tax accounts in Richmond County, and that of those, about 45% were Canadian non-Nova Scotia residents, 24% were American, and Europeans from German-speaking countries accounted for just over 30% of them.

Breeze concluded, among other things, that data on land ownership in the province is important for “land management and land use planning” and that information on the residency of landowners is also important.

The positive effects of non-resident land ownership were, she wrote, “seen to be economic” while the negative effects were “more wide-ranging.”

Among them were, “rising assessments and access to land for Nova Scotians.” However, there were also problems with the “purchases of popular waterfront properties, land that has been used for community activities.”

And, she wrote, “Land in Nova Scotia is being transferred to people who live here for only part of the year and who have no real stake in the local community. If we take the example of Richmond County, the question remains: if the full-time residents of Richmond County were well-off, had secure retirement funds, and higher per capital incomes, would they be selling their land?”

Prince Edward Island has long monitored land ownership

Breeze also looked at regulations in other provinces.

She wrote that Ontario, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia have all had legislation to try to regulate non-resident and foreign land acquisition, or preserve farmland.

But Prince Edward Island has done the most to regulate land ownership, with legislation to ensure that residents pay lower property taxes than non-residents, and to prevent concentration of large parts of the province in the hands of individual owners, either persons or corporations. Breeze noted that large landowners — among them Irving — were not happy with the legislation and publicly challenged it several times.

Breeze wrote:

Despite paying few taxes in the province, non-residents benefit from the taxes and services paid for by PEI residents even if they never set foot in the province, since “the availability of the whole spectrum of public services is an essential ingredient in contributing to the value of all properties within the provincial boundaries.”[2] Foreign owners benefit the most; they pay no taxes in Canada, other than property taxes, yet benefit from the stable land market and availability of services.

Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia both have relatively little Crown land. Only 12% of PEI is publicly owned and managed by the government, so the government pays close attention to how the rest of the province is owned, and taxed.

Spokesperson for the PEI Department of Finance, Kip Ready told the Examiner that the Real Property Tax Act and Regulations govern taxation of property on the Island, including of non-residents:

If you look to section 4 of the Act, it sets forth a tax rate of $1.50 per $100 of assessment on all non-commercial realty. Section 5 then provides a tax credit on non-commercial realty if the person assessed is a resident person or resident corporation. The tax credit is $0.50 per $100 of assessment, bringing the net provincial tax rate to $1.00 for residents. Section 24 of the regulations sets out the eligibility for the tax credit. It’s important to note that a non-resident is not taxed more (everyone is assessed at the $1.50 per $100 of assessment rate), but also that a resident is eligible for a credit that reduces the net amount owing to $1.00 per $100 of assessment.

Ready also explained that the Prince Edward Island Lands Protection Act (LPA) limits the amount of land that various owners can acquire:

-

a corporation or a non-resident person cannot have an aggregate land holding in excess of five acres or shore frontage in excess of 165 feet without first receiving permission from the Lieutenant Governor in Council

-

no persons, including residents, can have an aggregate land holding in excess of 1000 acres

-

no corporation, including residents, can have an aggregate land holding in excess of 3000 acres

Nova Scotia has no such regulations. If it did, Northern Pulp, which is ultimately owned by Paper Excellence and the corporate empire of the multi-billionaire Widjaja family of Indonesia, would not own 425,000 acres of land in the province, which Nova Scotians loaned the company $75 million to purchase in 2010.

Nor would Wagner Forest Management, an American investment company based in New Hampshire, own about half a million acres of the province — about 3.7% of Nova Scotia — which it purchased in 2006 from Neenah Paper, a spin-off company from Kimberly-Clark that bought the Pictou pulp mill from its original owner, Scott Paper of Pennsylvania, in 1995.

Nor would Irving concerns own the huge tracts of woodlands in the province that they do.

Nova Scotia has a limited amount of Crown land, according to the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables (formerly Lands and Forestry) website. “Only 35% of the Nova Scotia landmass is owned and administered by the province, compared to 50-90% in other provinces and territories.”

This means that 65% of the province is in private hands, which means any amount of that can be sold to anyone who has the money to buy as much of it — at least what is for sale — as they want.

Task force on non-resident land ownership

And this is why the issue never really seems to go away. Premier Houston’s mandate letter to his minister of finance looks like a case of déjà vu.

In April 2000, the Progressive Conservative government of Premier John Hamm introduced Bill 42, which contained measures that would have enabled municipalities to “levy additional property taxes non-resident property owners.” Although the legislation received Royal Assent three months later, the section on non-resident land ownership was not enacted.

Cabinet decided Voluntary Planning should “hold open discussions, conduct additional research, and provide recommendations on this topic.” Volunteers from the private sector came together to take on this task, and thus the Voluntary Planning Task Force on Non-resident Land Ownership was born. It held 17 community meetings throughout Nova Scotia between April and May 2001, and issued its final report in December that year.

Arthur Bull is past chair of the Coastal Communities Network, past chair of the Rural Communities Foundation, and past executive director of the Bay of Fundy Marine Resource Centre. He was also a member of the Voluntary Planning Task Force on Non-resident Land Ownership in Nova Scotia until a personal tragedy caused him to step off the task force.

In an interview, Bull recalled that while the issue looked “initially quite simple, it turned out to be anything but.” Said Bull:

First, the data on non-resident landowners was not solid, as many non-resident landowners in Nova Scotia had Nova Scotian agents with mailing addresses in the province. Second, many Nova Scotians own land in their home province, even if they don’t live there, and they reacted badly to the idea that they should pay an additional tax on property back home. And third, said Bull, is that the real estate industry had “a very strong influence” on the task force, and “put the kibosh on any kind of action.”

He said it was an “intensive piece of engagement.”

There were a lot of meetings and there were a lot of stakeholders and so forth, but nothing happened. That’s the outcome of it. They addressed the issue and didn’t do anything, which I think also becomes a kind of an interesting kind of case study for how we’re governed in general. There’s a lot of issues people want to be dealt with, but there’s often this kind of paralysis within government because of the complexity of the issue and because there are different pressures coming from different stakeholders. And so they deal with the issue in a sort of a symbolic way. They deal with it in terms of optics, and then just hope it goes away.

Residents make communities

Bull still believes the issue of non-resident land ownership should be closely monitored because there are implications for rural communities:

There’s a really critical difference, in my mind anyway, between non-resident and resident. Non-resident means you don’t live here. If you move here and live here for 12 months a year, you’re here, you’re a Nova Scotian, no matter what anybody says. You send your kids to the school, you pay your taxes. There is no two-tiered system.

It’s not about people from away, it’s about people who don’t live here … If there’s anything happening in the community, chances are they’re not going to be part of it, their homes are somewhere else. But that disengagement is happening across all of rural Nova Scotia. Basically government has withdrawn its services and its communication with the half of Nova Scotians who live in rural communities. There’s no more coastal communities network. There’s no more advocacy. The spaces for any sort of citizen engagement are gone. There’s Tim Hortons, basically that’s the space you get. So that’s already a problem. But it’s even more of a problem if people who own land are either not coming here or coming here infrequently, or even just coming in the summer; they’re not engaged. And so that’s not a good thing in terms of the whole political process.

Asked specifically about the marketing of Nova Scotia properties to moneyed people in Europe or elsewhere, Bull said that the issue of Germans buying land in Cape Breton was already attracting attention two decades ago when the Task Force was consulting on the question of whether non-residents should be taxed differently.

“That’s still happening,” he said. “But now everything is part of the global economy, everything is just so much more integrated now. Whether it’s land in Nova Scotia or New Mexico, or California, it’s all one big marketplace.”

“For somebody who sells a house in the UK, or Germany, or Toronto, they can come here and retire,” said Bull. In fact, he added, they will have enough money to buy a “sea captain’s mansion” in Nova Scotia.

Bull believes that one option the government could consider to even the playing field could be a rebate on property tax that is tied to household income.

“There’s no reason why John Risley needs a break on his land, or the Sobeys, or Jodreys, or Braggs,” said Bull. However, rebates tied to landowner income could help rural people who are feeling the pressure of the global economy and neoliberal policies driving the property market.

Bull doesn’t believe that any government will ever impose a property tax levy high enough to deter non-resident land ownership in the province, given the power of the real estate lobby. But he would like to see the province recognize the value of small communities and try to protect them.

Putting limits on individual land ownership as PEI has done, which could accomplish that, would take “really, really, really strong political will,” said Bull.

“We would have to start with the statement that we really think it’s important for young Nova Scotians or Nova Scotian families to put down roots here and we’re going to make it affordable for them,” he said.

But, Bull added, “I don’t hold my breath.”

Endnotes:

[1] Every person living in Nova Scotia who is not Indigenous is a settler, and all are living on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq People.

[2] The questions sent to the Department of Finance were:

- Is there currently a mechanism or system in place to identify which landowners in the province are not paying Nova Scotia taxes? If not, how would the levy be imposed? (I understand from Service NS that owner residency is disclosed by the owner at the time they purchase land, or their property is added to the land titles system that was launched in 2005. Non-residents of NS self-report this information. Is this a source of information in determining which landowners are not paying taxes in Nova Scotia? Or is this totally separate and irrelevant to a policy that would impose a levy on non-Nova Scotia taxpayers?)

- If so, what is the mechanism?

- Does the Department have a figure for the percentage of landowners in the province that are not Nova Scotia taxpayers? If so, what is the percentage?

- Is there an estimate of how much extra revenue this levy will generate?

- Will the levy on property taxes for non-Nova Scotia taxpayers stay with the Municipalities that collect property taxes?

[3] Antoft. K. 1992. Taxation and Non-Resident Property Ownership. A Report for the Department of Finance. Province of Prince Edward Island. 19 April.

Subscribe to the Halifax Examiner

We have many other subscription options available, or drop us a donation. Thanks!

It certainly isn’t just Cape Breton that is being sold off to moneyed people from around the world… this German-Canadian, Dr. Farhad Vladi, is president of VLADI PRIVATE ISLANDS GmbH, a company that purchases and sells islands off Nova Scotia (and around the globe) to those who can afford them [https://www.vladi-private-islands.de/en/islands-for-sale/canada-east/central] … does this look like 21st century neolberal neocolonialism?

Non residents pay an additional approximately 9% in NB.

A non-resident of Nova Scotia pays higher property taxes than a Nova Scotian who would own the same residential property. I could own 30 residential properties and my assessments for municipal taxes would be capped for as long as I am resident in Nova Scotia. It is a stupid system brought in by the NDP government of Darrell Dexter.

Capping was brought in because as coastal property values increased due to the influx of wealthy non residents, many older long time residents could no longer afford the increased taxes to keep their homes. Original residents who built homes on the coast and were part of a community for decades should not have been forced to sell and leave due to a heartless property market. The Dexter government responded to this oversight of market economics.