Greater risk of heat stroke. Increased spread of vector-borne illnesses like Lyme disease and dengue fever. Reduced cardiorespiratory functioning due to worsening air pollution. Drought, flooding, and melting ice that puts food and water security at risk.

While these are among the many widely known health-related impacts of climate change, Kathryn Stone’s research shows that when it comes to our changing climate, women are disproportionately impacted and so is their mental health.

“(Before starting this research) I had no idea the disproportionate impacts that climate change has on women. That was what I was most surprised about, particularly gender-based violence, which was a particular theme that I was interested in and shocked by,” Stone said in an interview.

“We know gender-based violence increases after enduring extreme weather events. But what about longer weather changes like drought, for example, where women have to go further into more remote locations to get resources?”

Earlier this year, Stone was the lead author of an article published online in the journal Current Environmental Health Reports called Mental Health Impacts of Climate Change on Women: a Scoping Review.

Stone, who graduated last October with her Masters degree in health promotion from Dalhousie University, said that while there were studies focused on gender and climate change, or on mental health and climate change, the review stood out because it identified studies looking at the mental health of women specifically in the context of a changing climate.

“To our knowledge, this is the first review that has explored both emerging fields together to uncover what is known about women’s mental health during the climate crisis,” the paper notes.

“Stigma of mental health is alive and well. A lot of our big climate reports, and even climate reports on health specifically, are starting to put a little tiny section about mental health in there, but it is nowhere near to the extent that the physical health implications of climate change appear,” Stone said.

“That is a gap, and I absolutely think research specific to women and climate change needs to be bolstered. Everything, in my opinion, should have a sex and gender-based analysis to ensure that we’re talking about climate change equitably.”

The findings of their study led Stone and her co-authors to state that in order to ensure women’s health and safety, there’s “a clear need” for climate policies on adaptation and mitigation that reflect the unique needs of women.

“From Australia, Uganda, South East Asia, to Canada, evidence suggests women face disproportionate climate-related threats to their socio-economic position, livelihood, food security, and health,” the paper noted.

“Furthermore, women have limited engagement in climate-related decision-making processes, preventing them from fully participating in climate policy, governance, and various aspects of climate governance and leadership. If women are not fully engaged in climate-related decision-making, we cannot expect that their needs will be met as climate impacts on human life begin to grow.”

‘Not just an acute weather event’

Stone said her reasons for pursuing this line of research were multifaceted, but her interest in the subject of climate change is longstanding.

Her Dalhousie University Masters thesis was ‘Understanding young women’s mental health in the changing climate in Nova Scotia, Canada.’ Submitted last summer, she said her work in this field was guided by professors Dr. Rebecca Spencer and Dr. Barbara Hamilton-Hinch.

“There was evidence of mental health challenges related to extreme weather — which we’re having more of — and extreme weather events specifically like floods and wildfires, and I started seeing the research about what these events can do to mental health,” Stone recalled.

“And then I was looking at research of longer-term climatic changes that can impact mental health. So, sea ice melting, hotter temperatures across the board, drought. There’s longer, chronic, persistent changes that we’re seeing. It’s not just an acute weather event that wreaks havoc, but longer things that aren’t going away.”

The authors noted that globally, post-disaster sites tend to be physically dangerous places for women.

In Bangladesh, women reported sexual harrassment following an extreme weather event while waiting in line for food and supplies. Women in High River, Alberta experienced increased rates of sexual assault following flooding there in 2013.

Another study noted that women and girls can face domestic and sexual violence after a disaster, “with adolescent girls reporting especially high rates of sexual violence and lack of privacy.”

After Hurricane Katrina hit the US in 2005, women surveyed from one internally displaced community reported a “significant increase” in gender-based violence. This further increased their risk of developing MDD (Major Depressive Disorder) and suicidal ideation.

In one Australian study, women expressed worry about what would happen following the next flood because of the increased incidents of domestic violence that occured in the aftermath of a previous one.

‘Women tend to bear the brunt’

“When there’s civil unrest, when there’s change, when there is some sort of burden on society or on a community, women tend to bear the brunt of that,” Stone explained.

What women experience in the aftermath of extreme weather events provides insight into what can be expected following more prolonged, climate-related changes.

“One study reported that because it’s often a woman’s responsibility to clean and cook and ensure family well-being, their work was significantly heightened after a major flood in Alberta,” Stone said.

“Similar to that, (with) ice melting in Inuit land in Nunavut (impacting hunting and travelling), women reported skipping meals, reducing the size of their meals, selling their personal items, all to keep their families fed at their personal cost.”

The review also noted that after the 2013 flooding in Alberta, there was an increase in the numbers of women getting prescriptions for anti-anxiety medications and seeking mental health services for depression and anxiety.

Women living in rural settings and with low socioeconomic status are at even greater risk for gender-based violence as a result of climate change. They also tend to face greater hurdles when trying to flee domestic violence.

In addition to gender-based violence and the burden of responsibility when it comes to caring for children and families, there were three other main themes highlighted in the study.

One of them was negative mental health outcomes. Stone points to studies from around the world that highlight women’s negative mental health outcomes specifically related to various aspects of climate change, including anxiety, depression, worry, stress, and sadness.

“There’s anxiety about food security too, and this is all related to our changing climate from Inuit land north of Canada, to floods in Nigeria,” Stone said. “They’re anxious about the health and safety of their children, anxious about water and water quality because of floods.”

Connection to land, culture, and tradition was another identified theme.

“We talked about women in Nigeria and the home and how that is such a special sacred place and a sense of comfort that can be totally wiped away by floods related to climate change,” Stone said.

“And then women in Fiji and New Zealand had to stop hunting and hiking and doing summer activities and traditional family things because of climate change, and they were particularly hurting and sad because of that.”

‘We are all in this together’

The final theme that emerged was the importance of intersectionality.

“I try and do everything with an intersectional lens, so then there’s a white supremacy racism component to all of this as well,” Stone said.

“We can talk about resource extraction near Indigenous communities and how that’s related to climate change and gender-based violence at the same time.”

Stone said climate change is closely related to colonialism and resource extraction, and there are many links that point to the necessity of following Indigenous leadership.

“Indigenous people make up about 5% of the world’s population, but protect over 80% of the world’s biodiversity, so land defence is something that we need to talk about more too,” Stone said.

“We need to talk about treaty rights and climate change. We need to talk about land rights.”

Stone said she’s moved by and often recalls the words of Nemonte Nenquimo, an Indigenous leader in the Waorani community in Ecuador who in 2020 was quoted in The Guardian as saying:

“We are all in this together. We need the world to recognize this,” Nenquimo said.

“This isn’t about Indigenous peoples fighting heroically and risking our lives to protect the land. This is about us all joining together across cultures, races and classes to change the way our global system works.”

‘Climate movement disproportionately white and male for a really long time’

Another key piece for Stone is the importance of inclusion in decision-making around the climate crisis.

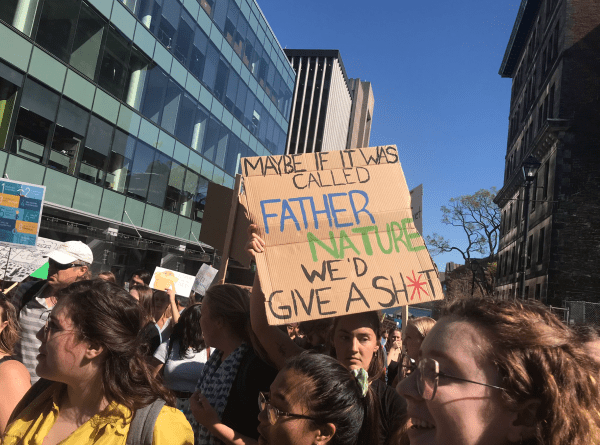

While looking at photos from the United Nations COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland last November, Stone said she was struck by the number of men in suits and how very few women were represented by comparison.

“In climate leadership they’re missing women, which has really significant impacts on our health because if we’re not at the table to make equitable decisions based on climate mitigation or climate adaptation, we might not be protected,” Stone said.

“The climate movement has been really disproportionately white and male for a really long time, and that needs to change.”

While women might not be well-represented in leadership, Stone said it’s important to note women are doing “amazing climate work” from community leaders at the grassroots level to women working for NGOs.

Despite the doom and gloom and hopelessness many people feel around the subject of climate change, Stone finds inspiration from people dedicating themselves to climate work and who continue to protect plants, animals, people, oceans, and other waters.

“That is what always inspires me and what makes me want to keep doing this work and what makes me want to keep thinking about it and keep doing things about it,” she said.

“It’s the antidote to eco-anxiety or eco-paralysis. Whether it be listening to podcasts, following people on social media, or just being involved in the conversation and seeing what folks are doing about this worldwide is really inspiring to me.”

No one-size-fits-all solution

What Stone wants health care providers to take from her work is an awareness of climate change impacts on women and to consider them when planning care for their patients, “especially young women who are seeing impacts of climate change from a young age and potentially experiencing them or afraid of experiencing them.”

“Climate change needs to be part of health work and health work needs to be part of climate change work,” she said.

She also wants to see more research about how mental health can be positively or negatively impacted by climate change. As one example, she’d like to learn more about something referred to as ‘post-traumatic growth.’ This is a phenomenon where people find healing, purpose, and community following an extreme weather event.

Stone also hopes her work opens up important conversations in the broader community.

“Climate change and the impacts of climate change are not distributed equitably, and that it is something we have to take with us when we’re talking about climate solutions whether that’s mitigating greenhouse gasses or adapting to our already experienced changes to the climate,” Stone said.

“We can’t dream up one-size-fits-all solutions. We need to see climate change as deeply intertwined with racism and misogyny and colonialism, and that is the only way we’ll be able to create solutions that truly work for everyone.”

Subscribe to the Halifax Examiner

We have many other subscription options available, or drop us a donation. Thanks!