Every year HRM pays Corporate Research Associates to survey people about crosswalk safety. To be honest, it’s mostly about whether or not the city’s ad campaigns are having any effect, but in 2014, the survey included basic knowledge questions on where pedestrians have the right-of-way crossing the street, legally speaking.

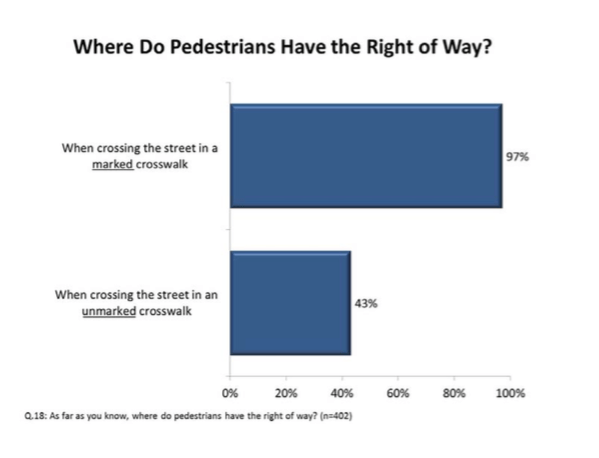

A stunning 47 per cent of respondents got it wrong, failing to check the box indicating that pedestrians have the right-of-way in an unmarked crosswalk. (Just in case any of those 47 per cent are reading this: In Nova Scotia and most of Canada, crosswalks exist at every corner of every intersection, and pedestrians have the right-of-way in all of them, whether they are marked or not.)

The next question on the survey was “As far as you know, does a crosswalk have to be painted for a pedestrian to have the right of way?” This time fewer people, a mere 30 per cent, made the same error, either answering “yes” or “don’t know.” (The answer, as per above, is no, and the 27 percentage point discrepancy between the two responses could indicate confusion over the terminology of the questions: Do people actually understand the terms crosswalk and right-of-way? Possibly not.)

Here’s what’s clear: almost everyone understands that pedestrians have the right of way in a marked crosswalk, but somewhere between 30 and 47 per cent of us don’t understand that pedestrians also have the right-of-way in unmarked crosswalks, and/or that unmarked crosswalks are everywhere.

I found this statistic disturbing in back in 2014. (I’d love to update you with the 2015 and 2016 numbers, but unfortunately, CRA dropped the question from their survey after 2014.) That’s a lot of people driving cars who are not prepared to yield to pedestrians when they should.

You can say this is an education issue, as did HRM’s manager of traffic, Taso Koutroulakis, as if more ads or better driver training could fix the problem. The thing is, I’m pretty sure police officers get more traffic training than the average licensed driver, and yet I’ve still met cops who don’t understand the simple rule that all intersections have crosswalks.

That’s because if we ever learned this rule, we started un-learning it as soon as we started driving.

Drivers are processing the information that is out there on the road. They are seeing marked crosswalks and thinking, okay, that’s where pedestrians cross. At the next block where there are no markings, they are assuming the opposite. The visual cues on the street actually tell us something other than what either driver’s ed classes or the Motor Vehicle Act do. That is, that there is a difference between marked and unmarked crosswalks. (There isn’t, legally speaking.) Because if they weren’t different, why would they look different?

Compounding the issue is our cheapness with our crosswalk markings. Only a fraction of our roughly 3,000 intersections in the city have a marked crosswalk. This year we have added or will add eight new markings, but we will also remove five. Every time a street is up for repaving, the city traffic department evaluates whatever is on the street and decides what they will replace after the road work is complete, and so crosswalks occasionally disappear.

Crosswalks removed this year:

- Breeze Drive at White Street

- Breeze Drive at Lethbridge Avenue

- Breeze Drive at Castleton Crescent

- Oceanview School Road (at the end of the road)

- Regal Road near Bayswater Road

Crosswalks (to be) added this year:

- Williams Lake Road at Ravenscraig Drive

- Washmill Lake Drive at Main Avenue

- Regency Park Drive at Thomas Raddall Drive

- Beaufort Avenue at Oakland Road

- Beaufort Avenue at Inglis Street

- Chebucto Road at Benjamin Green

- Brunswick Street at Gerrish Street (aka Divas Lane)

- Baker Drive at Freshwater Trail

Then when we do mark a crosswalk at an intersection, we often just mark one leg. The differentiation between the marked and the unmarked crossing ends up interpreted as differentiated right-of-way within the same intersection. And so drivers might yield to pedestrians in zebra stripes on one side of a crossing, but will whizz by anyone attempting to cross on the other side.

The whole situation adds up to reduced efficiency and connectivity for pedestrians. And it also helps create the confusion and misinformation around where exactly drivers should be yielding to pedestrians (i.e., at every intersection).

Taso Koutroulakis thinks this is bunk. He puts it much more politely, though:

“I would respectfully disagree,” says Koutroulakis.

“In theory you could put a marked crosswalk at every location at every intersection on the peninsula. In theory. But then you have to look at it. You have to highlight the areas that are special. You have to give motorists a cue that this is an area to expect an increased number of pedestrians. Because if you were to paint a crosswalk at every location, you just become desensitized with respect to the importance of it.”

The idea of desensitization on the part of drivers comes from experience with stop signs, says Koutroulakis, though he admits he doesn’t have a specific study to support the idea. “Whatever the traffic device is, the proliferation of stop signs or crosswalks or whatever… The motoring public will not respect the device that is placed. We’ve seen that in stop signs. You see in those locations where stop signs are not warranted, you see vehicles roll through the stop, which is a concern.”

I totally agree that cars rolling through stops is a concern, but marking a crosswalk is significantly different than adding a stop sign. Marking a crosswalk changes exactly nothing about the rules of the road. The obligation to yield is already there, white lines or no. The markings simply delineate space for pedestrians across intersections, and give a visual cue to drivers that there are sidewalks on either side of them as they pass through.

The myth of the emboldened pedestrian

Curiously, almost all of the research on marked versus unmarked crosswalks focusses exclusively on pedestrian safety. There may be a study out there that looks at the effect of the number of marked crosswalks on the number of people walking in a city or how long it takes them to get around, but I couldn’t find it.

But let’s consider the safety studies, because it is, after all, pretty damn important to avoid getting injured or killed on your way to the store.

A study published by the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) in 2005 sums up the past research on the subject this way:

Studies of the effects of marked crosswalks have yielded contradictory results. Some studies reported an association of marked crosswalks with an increase in pedestrian crashes. Other studies did not show an elevated collision level associated with marked crosswalks, but instead showed favorable changes.

One of the original studies to show possible negative safety effects was done by Herms in 1974 in California. Sadly, the oft-quoted part of this study is the idea proposed by its author that the worse crash records for marked crosswalks were “a reflection on the pedestrian’s attitude and lack of caution when using the marked crosswalk.”

And thus the myth of the emboldened pedestrian was born.

I say myth, because as the USDOT study, by Zegeer et al, explains: “The Herms study, however, does not say what evidence the author had in mind regarding incautious pedestrian behavior. No behavioral data was presented.” But the idea had legs, and continues to be advanced as a possible explanation whenever a study shows increased crash rates at marked crosswalks. Ultimately though, it’s supposition, and doesn’t really stand up to the evidence, since markings do not always increase crash rates.

So if it’s not pedestrians rendered careless by white lines on the road, then what does account for the increased crash rates found in many studies? The Zegeer study, entitled “Safety Effects of Marked versus Unmarked Crosswalks at Uncontrolled Locations,” tries to get to the bottom of it. One of the big reasons for the contradictory results among studies, Zegeer concludes, is that they are not adequately controlling for different types of streets, with different numbers of traffic lanes, and different traffic volumes.

Zegeer’s study of 1,000 marked and 1,000 similar unmarked crosswalks over five years found that on busy multilane roads, a marked crosswalk alone (with no other improvements such as lights or raised medians) would increase the crash rate. But Zegeer also found that for two lane roads, or multilane roads with fewer than 12,000 vehicles per day, marked crosswalks had no significant effect on crash rates either way. They were effectively neutral, in terms of safety. (To give you a sense of those numbers, Almon Street between Robie and Windsor sees just shy of 12,000 vehicles per day. Other sections of Almon see as few as 5,000.)

So, according to Zegeer, we shouldn’t be just painting lines across Joseph Howe Drive and hoping for the best. But, as the study’s introduction opines: “Failure of one particular treatment is not a license to give up and do nothing.” Rather, we should be amending those crosswalks with additional treatments such as curb bump outs, raised medians, raised crosswalks, and/or lighting.

But perhaps most important to my point: Zegeer also concludes that there’s no safety reason not to simply paint more lines on our two lane or less busy streets.

You might wonder, though, if there’s no significant improvement to safety, then why would I even want marked crosswalks all over the place? Well, sometimes, just sometimes, pedestrian infrastructure is not just about safety. Sometimes it’s about access and efficiency.

Pedestrian efficiency matters

There’s pedestrian safety, and then there’s pedestrian level of service. The two may or may not always coincide. It’s the same with cars. We all know that the safest way to use a car is to keep it parked in your driveway. Yet hordes of us get in them every day and drive around. Why? Because we are living people who need to get from A to B. It’s the same with pedestrians. Sure, it would be safer not to walk at all, and if you are walking, to just never cross a street. But come on, it’s time we acknowledge that walking (or rolling) is about getting from A to B just as much as driving. (On the peninsula, there are areas where 50 per cent and 60 per cent of people are commuting by either walking or biking, with the lion’s share walking.)

Knowing this, it’s the job of city planners and engineers to make it as efficient and safe as possible. I know… gasp! I am putting efficiency right up there with safety as a factor for pedestrian infrastructure. Why not? We’ve been doing it for decades in vehicle infrastructure.

Engineers have even established formulas to measure what is called Level of Service (LOS) for people in vehicles. It’s essentially an efficiency measurement… the longer the wait time at a crossing, the more crowded the road, the lower the LOS. They even assign grade levels, and make actual decisions based on them.

In the pedestrian arena, however, our decisions are almost exclusively based on safety. It’s as if we are saying people in cars need to get places efficiently, and people on foot just need to stay alive. (It’s going to take you five minutes longer to get to work every day, but hey, you will not be crushed by a car.) And that thinking has landed us with a city that is built to maximize vehicle traffic flow and connectivity, with very little concern for the flow and connectivity of its pedestrian network.

I should certainly mention here that Taso Koutroulakis did mention pedestrian connectivity in among the factors considered for whether or not to add or remove markings for a crosswalk. But one has to wonder how much weight connectivity is given as a factor when there is still no marked crosswalk across Quinpool Road at Monastery Lane. (“That’s something we are looking at,” says Koutroulakis.)

Or when the city continues to mark a only single leg of an intersection across a busy pedestrian street like Spring Garden Road. Or when a requested crosswalk across Windsor Street near the forum is rejected.

There’s no formula to determine where marked crosswalks appear and disappear, says Koutroulakis, but things like the number of pedestrians currently crossing at a location plays a part. Crosswalk safety advocate Norm Collins has been known to take issue with the decisions around where to mark crosswalks. His request for a markings across Windsor Street near the Forum was rejected, he says, because not enough people were already crossing there. “More people would use it if it was marked,” say Collins. “So assessing it that way doesn’t make any sense to me.”

“In the engineering profession,” says Koutroulakis, “we use our best engineering judgement to determine where a device is most appropriate on a roadway, whether it’s a crosswalk, a signal, or a stop sign. Yes, we have guidelines but at the end of the day it’s engineering judgement.”

Now I get that there’s a whole lot that goes into becoming an engineer, but we have to acknowledge something important here. The judgement of engineers is generally based on the assumptions of the field. And it’s what has built the city we currently have. It’s not that I want the opinion of laypeople to trump the judgement of engineers. It’s that I want engineers to question their own judgement, on a daily basis, as part of their profession. I want them to shed old chestnuts like the myth of the emboldened pedestrian. I want them to look at a problem like 57 per cent of people thinking there are no unmarked crosswalks, and wonder if there is something they are doing to help create that problem.

The assumptions behind the judgement of engineers have landed us squarely where we are. So if we agree the status quo is not okay, then we need engineers, and loads of other professionals, to challenge and change their own assumptions.

Regsrdless of cost, pedways in particularly dangerous areas are the ultimate. Really disgusted that this proposed safety crossing opposite Dartmouth’s bus terminal bit the dust due to unsurprising cost over-runs. Considering the cost of enginee evaluations, build at least a pedway or even two. Paint every crosswalk spring and fall. Plant orange flags at every stupid invisible crossway. Forget debating whose abusing whatever rule because crosswalks are supposed to be safe crossing. Period

It’s not just cell phone oblivion, it’s also the speedy aggression rampant in society where people just want to get their way. And they ignore common sense to do to. Around the Dalhousie area there are innumerable times I have been at a traffic light, and had someone ignore a no-walk sign, step out against a light, and brazen their way across the street. This happened on South Street at South Park where a runner ran out in front of my car [when I had a green light and was turning left] and I hit them! (One of the most terrifying moments in both our lives). Thankfully they were not seriously injured. When the police arrived on the scene they gave the RUNNER a jaywalking ticket. In Copenhagen it is a city law to wear clothing marked with reflective gear during their long dark winters. Might be a good idea here as well, although it would not have prevented this accident or others which spring from a base sense of entitlement.

What ever happened to the following advice, meant to ensure pedestrians can cross safely — ‘Stop, look both ways, make eye contact with the driver of the approaching vehicle (i.e. if there is one) and, when the vehicle slows to stop, proceed to cross when it is safe to do so’?

On rare occasions on busy roadways where there is a heavy stream of traffic, pedestrians also have been advised to extend an arm out horizontally to clearly indicate his or her desire to cross, and process when the driver of the approaching vehicle responds by stopping and it is safe for the pedestrian to proceed.

I follow these simple procedures every time and I have not experienced had any difficulties or near misses, and don’t expect to any time soon.

Exactly ADS!

Looking both ways twice and always proceeding with caution was how we were told to cross as kids. I’ve been crossing railway lines, lanes, streets and highways for well over fifty years now and not once have I caused an accident or been hurt by following this simple advice. The McNeil government passing anti-jaywalking legislation that would impose a ridiculous $697.50 fine on people crossing safely using due caution and their common sense is a nothing more than crude political point scoring – being seen to ‘do something’ about pedestrian-vehicle accidents, even if in fact it’s actually useless (apart from making money).

Sure there are careless drivers and pedestrians out there, but ultimately you can’t legislate away stupidity. Nobody who is too lazy to look up from their smart phone while crossing a street is going to consider a jaywalking fine.

My $CD 0.02

Looking both ways is only half the battle for the pedestrian. Many many many vehicle-pedestrian incidents involve cars making LEFT turns where you can’t easily make eye-contact with the driver — this is also just about impossible when there are several lanes of traffic with drivers all arriving at different times to the intersection — not exactly the focus of this article but a big problem nonetheless. I’d love to see HRM do what’s done in parts of Quebec — where all drivers at a busy intersection get a red light and pedestrians can cross in any direction they want — including diagonally. They work really well.

Is any thought given to comverting crosswalks to stop signs or traffic lights? I’m guessing that would never pass muster in this car-centric town. Maybe if we de-amalgamate (ha!).

I find the crosswalks to be a half-measure. If possible, I stick to crossing at traffic lights, although I’ve still had some near-misses — Robie and Spring Garden, I’m looking at you.

Thanks once again for shedding the light of common sense on the experience of getting around Halifax on foot.

That SGR/Brunswick crosswalk was life-changing. But you’re right, there should be one at both corners. I think drivers would appreciate that, too, because they often get stuck as a stream of people coming from the west have to cross Brunswick before using the crosswalk. Also, cars turning left or right onto SGR would have more chances to do so, as presumably fewer people would be crossing one or the other at a given time.

The Quinpool problem is mystifying. It’s like the city still considers Quinpool a suburban street. Or thinks that people the West End and the South End should each keep to their side. Also, those planters in front of the Superstore/Canadian Tire/LC?!

While I’m at it, I’d like to point out the urgent need for a crosswalk on Cogswell between Maynard and the municipal parking lot/dog park. It’s time the city acknowledged that people (by which I obviously mean ME, but also area residents and commuters who park in the North Commons area) routinely cut through the lot and up the stairs to Rainnie.

Ah but the planters on Quinpool Road, provide seats for the smoking lounge for Superstore employees and panhandlers.

Great article, Erica. I find it interesting just how few crosswalks were added. I would assume a much higher number.

I also think we need to end the mythos of “the engineer”. Traffic Engineers are bright and considerate people who work with numbers, not people.